The Great Stink of 1858: How a Smelly Summer Changed London Forever

London in the summer of 1858 didn’t smell like a grand capital. It smelled like a mistake that had been simmering for centuries. The River Thames, famous for commerce and poetry, had turned into a slow, brown broth of sewage and heat. You couldn’t stroll the riverbank without gagging. You couldn’t open a window near Westminster without instantly regretting it. The odor bullied its way into Parliament and turned powerful men into queasy ones. Newspapers gave the crisis a name that still makes people wrinkle their noses: the Great Stink.

Why the Thames Stank: London’s Sewage Crisis of 1858

For generations, Londoners had treated the Thames like a bottomless trash can. Household waste, animal offal from slaughterhouses, chemical runoff from factories, and the daily output of a booming population all poured into the river. The city continued to grow, the waste continued to multiply, and the old habit of letting the tide carry it away persisted, masquerading as a plan.

Then came a hot, dry summer. Less fresh water flowed to push anything out to sea. Heat turned sluggish stretches of the river into giant stewpots. Bubbles rose through a surface filmed with grease and refuse. The smell didn’t just drift. It clung. People swore they could taste it. The Thames had become a working example of what happens when infrastructure falls way behind reality.

The Great Stink Reaches Parliament: London Holds Its Nose

Londoners were used to foul smells, but 1858 hit differently. The stink invaded Parliament itself. Clerks dabbed handkerchiefs with vinegar. Staff hung curtains soaked in chloride of lime. These weren’t quirky Victorian remedies — they were desperate moves to keep people from vomiting at their desks. Debate slowed, then stalled completely. Newspapers reported MPs leaning away from their benches as if an extra inch would make a difference. The joke on the street was that the river had finally figured out how to lobby.

For years, reformers had argued the city needed a proper sewer system. Cholera had already swept through several times, and evidence was mounting that contaminated water was the real culprit. Still, nothing happened. Big projects are easy to delay when they cost money, and the suffering mostly lands on someone else. The Great Stink changed all that. It’s hard to ignore a problem when it barges into your office and slaps you in the face.

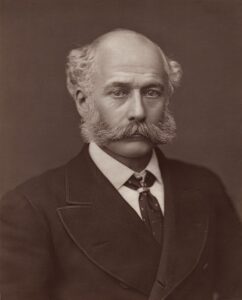

Joseph Bazalgette and the Sewer Plan That Saved London

That’s when Joseph Bazalgette, Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, took the stage. He wasn’t flashy. He was an engineer with maps, math, and a plan. Bazalgette had been pushing for a modern sewer system for years, and now, with noses in open revolt, Parliament finally opened the purse strings.

His design intercepted waste before it hit the central Thames and moved it downstream to outfalls far from the city. It included more than 80 miles of main sewers, over 1,000 miles of street sewers, and pumping stations built like brick cathedrals. He even oversized the pipes, figuring London would keep growing. That bit of foresight is why much of his system is still in use today.

Cholera, Bad Air, and the Deadly Stakes of London’s Great Stink

It’s easy to laugh about the smell, but the stakes were deadly. Contaminated water had fueled cholera outbreaks that killed tens of thousands. At the time, many still believed in “miasma theory,” the idea that bad air spread disease. Even if the science wasn’t entirely correct, rerouting waste away from drinking water made the city far safer. Sometimes, luck and engineering prevail over shaky theory.

The Legacy of the Great Stink: How London’s Sewers Changed the World

The results came quickly. Water got cleaner, cholera cases dropped, and other cities started copying London’s playbook. Bazalgette’s sewers became one of the most important public works projects of the century. Every flush in modern London is still, in a way, a thank you to him and the team that built for the future.

The Great Stink also changed the politics of infrastructure. It showed that big systems aren’t luxuries. They’re the invisible skeleton of a city, and when they fail, everything fails with them.

The Human Side of the Great Stink: Smell, Politics, and Progress

Part of why the Great Stink sticks in memory is that it feels like satire. On one side, lawmakers gagging behind lime-soaked curtains. On the other, engineers calmly digging tunnels and laying pipes. There was no heroic showdown, just brickwork and foresight. But those quiet fixes saved countless lives and reshaped London.

What the Great Stink of 1858 Teaches Us About Cities Today

Stand along the Thames today and you’ll see joggers, tour boats, and water that actually supports wildlife again. The smell of 1858 is gone, but the lesson lingers. Sometimes change comes from a great idea that inspires people. Other times, it comes from a crisis that makes breathing unbearable. Either way, progress is progress.